Immigrant Heritage Month and BIPOC Mental Health Month

Publisher: ICOY Staff

June was a month to celebrate immigrants and their contributions to community and culture in our country – Immigrant Heritage Month. And as July comes to a close, it was a month to heighten awareness of BIPOC Mental Health. Growing up in central Illinois, there weren’t a lot of Filipinos. There were enough that when I would visit my parents working at the hospital, I’d inevitably greet a “Hi, Tita!” or “Hi, Tito!” in a hallway. There were enough that our tight-knit community gathered for summer potlucks that were held in large park district facilities, religious celebrations that often concluded in the school gymnasium or cafeteria with trays of food, and holiday parties that featured traditional Filipino dances in addition to filling the floor and dancing to typical American pop-music. Regardless of the reason of the get-together, we gathered to appreciate our community and celebrate our space.

As a first-generation Filipino-American, I have great respect for my parents and countless others that left their homes and families. They started a new chapter and adapted their sense of identity in a completely different setting. I am fortunate to inherit their courage and strength. I also recognize the special challenges that first-gens endure. We are the bridge. On one side, we have the life and traditions of the homeland. On the other, we have the want, and sometimes need, to assimilate into the new setting. Sometimes this assimilation is out of fear that all generations would face the on-going effects of racism and discrimination towards the immigrant community. And sometimes standing on this bridge allows for inter-generational trauma to continue. Just as awareness months change over time, we can take time to celebrate our heritage and take time to protect our mental health.

FILIPINO FOOD AT HOME

I have had a lifelong love/ hate relationship with food for many reasons, one of them being a fear of racism. Starting at a young age, I was fortunate that my dad grew a wide variety of vegetables in our back yard, even those uncommon in central Illinois. Because some of these vegetables weren’t discussed in school and didn’t look like anything we’d find at Kroger, I didn’t know how to identify them. One of them, he called bitter melon. Another, he named “green stuff.”

I often thought he changed the names for me because my parents didn’t teach us Tagalog or Ilocano. It turns out bitter melon is the real name – imagine my surprise when I saw it in grocery stores later in life! “Green stuff” is upo, a green squash that cooks well with onions, garlic, ground beef and tomatoes. For the most part, the available vegetables would guide our meals, and to this day, he still grows a wide variety. (My lack of knowledge of my parents’ native languages is another part of the assimilation topic that we’ll save for another day.)

With that context, it seems on-brand that our family wouldn’t have the typical foods on-hand that most grade schoolers enjoy. I didn’t try spaghetti-o’s until I was in 8th grade and our cabinets were rarely home to fruit snacks or pudding cups, though we did enjoy soda. Again, I recognize that I was very fortunate that my parents cooked nearly every meal for us. This also meant that I had memories from grade school of being fearful of inviting friends to the house. What would we eat? Does the house smell like adobo? Is that bad? What if they want a snack? And where did I even learn these fears? On one hand, I loved and still love my parents’ cooking and Filipino food, in general. On the other, as a child, it felt strange to not share something that I held in such high regard.

BUKO SALAD, OR FILIPINO FRUIT SALAD

When I reflect on my childhood, I recall points in time when I started to want to celebrate my heritage. In-between grade school and high school, I tried out for my high school dance team and made it. Again, looking back, I think I recognized being on the team allowed a safer, more comfortable entry to a new school. Practices started over the summer, so I became familiar with the campus and bonded with my twenty-some teammates.

I remember we had a potluck dinner to kick-off the year, and we signed-up for our contribution. I saw “fruit salad” as an option and, having helped my mom make fruit salad numerous times for Filipino gatherings, I put my name down. (Full disclosure: when we make it similar to the recipe in the link, our family tries to use fresh fruit!) I hyped it up to my teammates during practice, mentioning the ingredients and how much I loved it. Then the day came, and we were at the potluck. My mom decided to make an American version of fruit salad – not the version I had talked about during practice.

I felt silly for being excited to share it. I felt ashamed that my mom did not want to make the Filipino version. The disappointment in whitewashed fruit salad closed me off. I was quiet for most of the night. When I asked her why she didn’t make the “normal” version, she said she didn’t realize that’s what I’d wanted. But if that was only version we’d ever made, that was my only reference. And in many Asian-American and first-gen families, these situations and feelings weren’t openly discussed, further causing confusion in my confidence in my identity and pride.

Fast forward to adulthood when more people seem to love Filipino food. In some areas it’s popular to enjoy breakfast comfort food of garlic fried rice, over-easy eggs, and longanisa. The crisp edges of slow-roasted lechon or fried lumpia. The vibrant purple in anything ube that’s any Instagrammer’s dream. Again, on one hand, I’m happy for the next generation. They don’t face the same level of fear of embracing cultural food. On the other hand, I’m not yet healed that my parents and generation were made to feel that those beloved foods are disgusting and unwanted. And the fight continues. There was recently a petition to James Corden to stop using Asian-centric foods for his sketch, Spill Your Guts. Read more on this from The New York Times.

LEARNING THE HISTORY & CULTURE

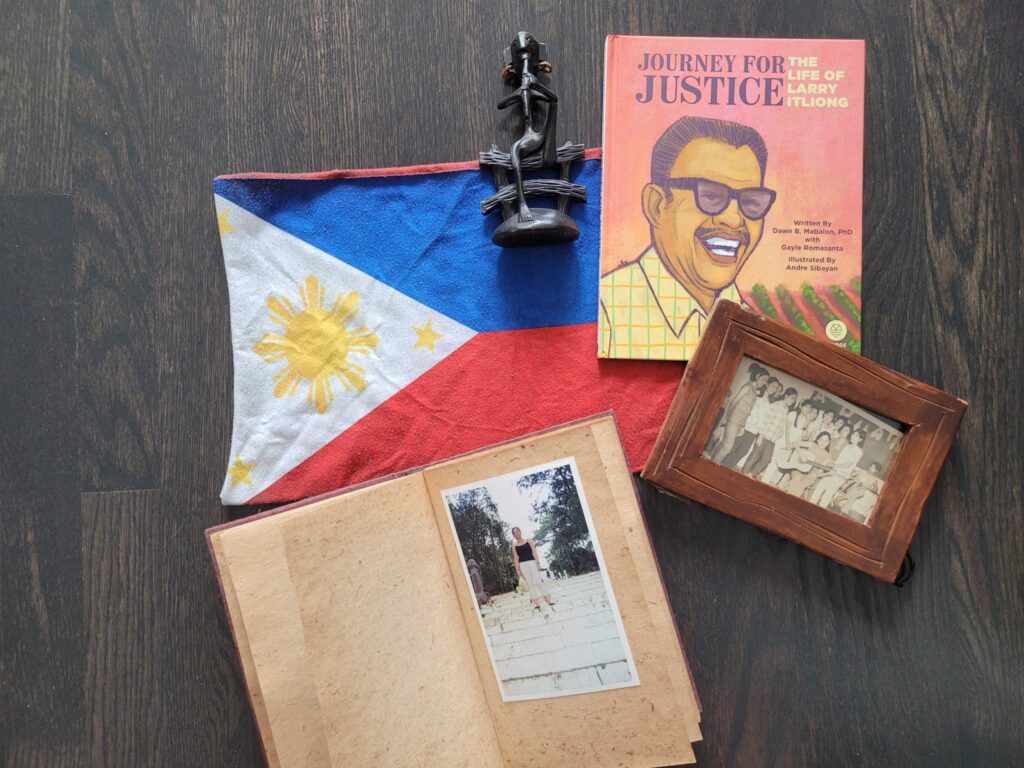

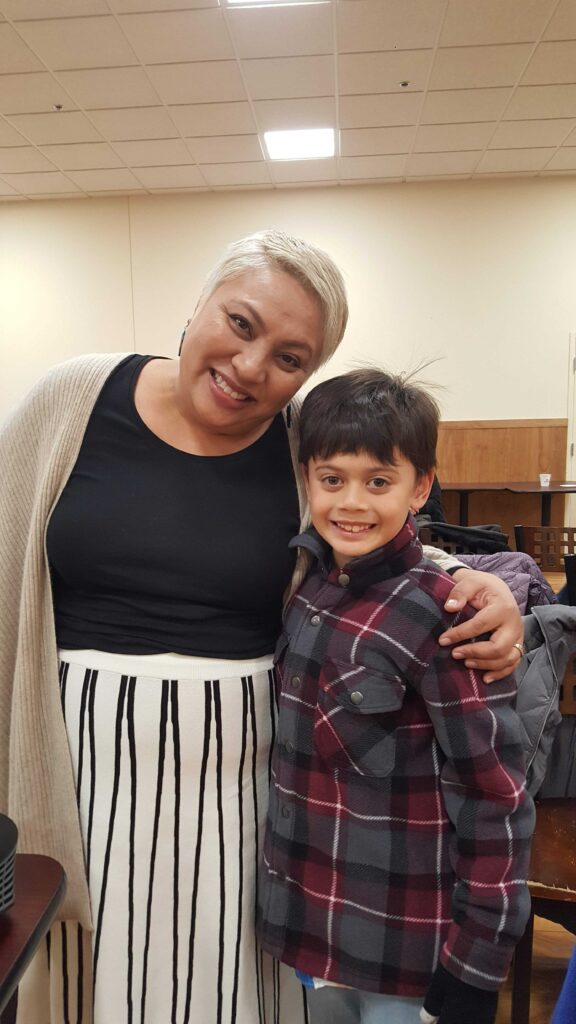

Now, I have a son of my own. As a constant celebration of our history, we work together to learn more about our Filipino heritage. We try cooking recipes together at home, and when they can visit, he cooks with my parents. He and I make the effort to visit Filipino-owned businesses. When possible, we try to attend events. But it saddens me that he hasn’t enjoyed some of the experiences that were in my childhood. He hasn’t learned traditional dances as I did at his age. It wasn’t until my 30’s when I brought him to a book signing event, where we both learned for the first time about Larry Itliong and his large part in creating the United Farm Workers union with Cesar Chavez. My son hasn’t had the opportunity to visit the Philippines, but we do hope to make that trip in the future.

I love and adore that my son wants to celebrate his heritage. And like most things, it takes time and consistent effort, not just one month, to continue to learn and grow. When I think about “awareness months,” I hope that they serve as a starting point to that consistent effort. I hope that we all consciously schedule time to learn more about our own heritage and appreciate our contributions to our culture, even if we’re made to think otherwise. Celebration of culture and first-gen issues are all points of discussion that have surfaced during my therapy sessions. And as my therapist is also a Filipina, they also have similar first-hand experiences.

Shortly after Immigrant Heritage Month the nation celebrated Independence Day and then BIPOC Mental Health Month. I choose to celebrate my culture and in that, I pause to participate in the celebration of separating from the original colony. Because in celebrating Filipino history and those of many other immigrant communities, we see that even though the first-generation colonizers set-out to separate themselves from the control of a far-off country, they also repeated history, in the opposite role.

Can we reimagine the idea of freedom? Can we build towards the idea of living our lives as we want to live them, without systems built against us? Where the tired, the poor, the huddled masses can breathe free? Every time I meet someone who is working to dismantle the systems of oppression and white supremacy, I celebrate. I appreciate organizations like ICOY that work toward a brighter future for generations to have the potential to celebrate independence from systems that were created to prevent them from fully living. It gives me so much joy to have role models like Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles who have shown the strength and courage to choose their health over the needs and wants of others. It gives me hope that we will be the generation to actively work on breaking traumatic cycles and prioritize healing.

– Melissa Franada, Communications & Marketing Manager

Upcoming Events